Have you ever wondered how you can enjoy the flavor and health benefits of the Mediterranean diet if you don’t live in the Mediterranean region and can’t get many Mediterranean products where you live? Scientists have not forgotten you. They have come up with an answer in the form of a “Planeterranean Diet” that adopts key concepts from the famous Med diet.

The “Planeterranean Diet” is defined as “the Mediterranization of local food systems: adaptation to a ‘locally produced, locally consumed’ diet” in the program of the 1st International Yale Gastronomy & Culture Symposium that took place in Heraklion, Crete May 3-4, 2023. One of the symposium’s most intriguing panels addressed the adaptation of a Mediterranean nutrition paradigm beyond its native region, and the way this can extend the Med diet’s benefits for human health and the environment to people around the world.

You have probably heard of the Mediterranean diet, since US News & World Report designated it “the Best Diet Overall” for six years in a row. This diet’s nutritional benefits are well known, and it offers even more. Referring to an article in The Lancet in her symposium presentation, Dr. Antonia Trichopoulou of the Hellenic Health Foundation explained, “in epidemiology, it is rare to have such consistent evidence of the beneficial effects” as what scientists have discovered regarding the Mediterranean diet. It is “a diet that maximizes longevity, improves health-related quality of life, and is ecologically sustainable and environmentally friendly.” A largely plant-based diet, its most common foods can be produced with limited water and substantial CO2 absorption.

As Trichopoulou pointed out, “since 2010, the Mediterranean diet has been included in the UNESCO list of the intangible cultural heritage because it is a way of life, a lifestyle” that includes “many skills.” Part of the region’s tradition, it is closely connected with culture, “from farm to table.” It developed over thousands of years “in the Mediterranean basin where we have the olive tree, because without the olive tree, without olive oil, we cannot discuss the Mediterranean diet.”

Given its numerous benefits, Trichopoulou reports, “many populations around the world try to mimic the Mediterranean diet,” or at least adopt some of its practices. In various regions, people are beginning to “find their own ingredients, their own legumes, their own vegetables” that grow in their areas and fit their needs, climatic and economic conditions, and gastronomic traditions. She is glad to see this “movement on a global scale,” because she believes “what God and nature offered us we should disseminate all over the world as a message in terms of public health; we can offer the benefits to any citizen.”

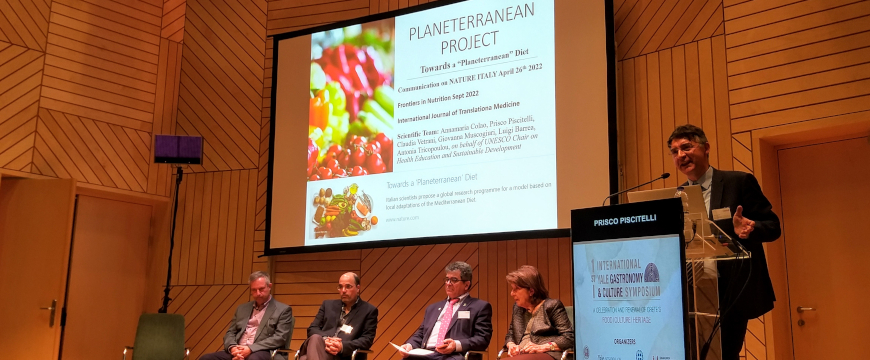

Dr. Prisco Piscitelli, epidemiologist at UNESCO Chair for Health Education and Sustainable Development, Federico II University, in Naples, Italy, has been working with Trichopoulou and others on the Planeterranean Project. In it, “scientists propose a global research program for a model based on local adaptations of the Mediterranean diet.”

As one of their 2022 articles explains, the goal is to extend “worldwide the health benefits of Mediterranean Diet based on nutritional properties of locally available foods … to prompt each country to rediscover its own heritage and develop healthier dietary patterns based on traditional and local foods.” Starting with the Mediterranean diet, which is associated with “reduced prevalence of cardiovascular, metabolic or neurodegenerative diseases and cancer,” the researchers also aim to “help preserve biodiversity and natural resources, as well as cultures or traditions” in each location.

The Planeterranean Project team is working on “nutritional pyramids for different areas that have similar benefits to the Mediterranean diet, adapted to local cuisines,” yet with a notable resemblance to the Mediterranean diet pyramid Trichopoulou helped develop decades ago. The aim is to identify appropriate “vegetables, fruits, cereals, and unsaturated fats available in different parts of the world.” For example, wholegrain quinoa in Latin America and barley in Asia are low-glycemic index, high fiber options. Polyphenols and other phytochemicals are found in pepperberry in Oceania, soy and sesame in Asia, and pecans in North America.

Other scientists on the same symposium panel discussed comparable efforts to extend the benefits of the Med diet, or something comparable to it, to people on various continents. Dr. Jean-Claude Moubarac of the Department of Nutrition at the University of Montreal introduced a movement of resistance to the global spread of unhealthy ultra-processed foods, which includes an effort to protect and support traditional food cultures. For example, projects in Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, and Peru promote cooking and eating together according to certain recommendations. Relying on traditional recipes, a diversity of foods, less meat, more fresh food, and fewer highly processed foods, these recommendations resemble the practices of the Mediterranean diet.

Dr. Guansheng Ma of the School of Public Health at Peking University presented a Chinese Food Guide Pagoda that looks a lot like the Mediterranean diet pyramid, except that it has “oil” at the tip, rather than an abundance of olive oil closer to the pyramid’s base. Ma explained that the Jiangnan diet pattern recommended in China is similar to the Med diet in various ways: it is a balanced diet with whole grains, fish and shrimp, “abundant fresh fruits and vegetables in season, minimally processed foods.”

Advertised as “a celebration and renewal of Crete’s food / culture / heritage,” the Yale Gastronomy & Culture Symposium and its Planeterranean Diet session sometimes seemed to pull listeners in two different directions. On the one hand (as in the talk by Dr. Michalis Katharakis of the Regional Council of Research and Innovation in Crete), it valorized the specifically Cretan version of the Mediterranean diet and its particular value. On the other hand (during most of the session), it explored various versions of Mediterranean-style diets adapted to fit the local food offerings and cultures around the world to improve health globally. The vast nutritional benefits of the Cretan version of the Med diet, with olive oil at its center, were mentioned--even assumed--but the reference to other cultures’ foods, including oils that lack many of the health benefits of extra virgin olive oil, did not settle the question of the role olive oil should play in healthy diets.

During a discussion after the panel’s presentations, symposium organizing committee member Aris Kefalogiannis, an innovator and entrepreneur in fine foods, pointed out that a Gaea company-funded study had determined that 70% or more of the carbon footprint of foods tends to come from fertilizer, not transportation, even from Greece to the USA. So 1 kg of olive oil has a 4.18 kg carbon footprint when transported that far, but locally produced tomatoes have 35 kg and locally produced beef 70 kg. As Kefalogiannis concluded, even when it must be shipped a long distance, “olive oil is still a very environmentally friendly product.”

In comments to Greek Liquid Gold after the symposium, Kefalogiannis admitted, “in order to create the Planeterranean diet, or more precisely to Mediterrranize local food systems internationally, we have to heavily rely on locally produced food products. For two reasons: firstly to make it easy and affordable for local people to adopt the Mediterranized local diet, and secondly for reasons pertaining to environmental sustainability.”

However, Kefalogiannis would not go as far as some members of the panel to an approach that could “dilute the goal of Mediterranization of local cuisines and the numerous health, wellbeing and sustainability benefits that should be expected by the Mediterranization process.” He believes “Mediterranization is impossible without some essential ingredients that constitute the cornerstone and very essence of the Mediterranean diet,” identifying extra virgin olive oil as “the most indispensable” component.

Why? According to Kefalogiannis, “extra virgin olive oil, besides being the world’s most healthy fat, with numerous health benefits and recognized health claims, makes raw and cooked veggies and pulses tasty and creates an overall balanced diet. In addition, thanks to its extremely low carbon footprint, from field to fork, or even negative carbon footprint if we include in our estimation of the carbon footprint the negative CO2 sink that the olive groves present, it transports very well and can play the protagonist’s role, complementing local produce, that is necessary for the Mediterranization of local cuisines.”

As Trichopoulou asserted in her presentation, “without the olive tree, without olive oil, we cannot discuss the Mediterranean diet.” What about the Mediterranized diet? That could be a topic for a future session.

All businesses, organizations, and competitions involved with Greek olive oil, the Mediterranean diet, and/or agrotourism or food tourism in Greece, as well as others interested in supporting Greeks working in these sectors, are invited to consider the advertising and sponsorship opportunities on the Greek Liquid Gold: Authentic Extra Virgin Olive Oil website. The only wide-ranging English-language site focused on news and information from the Greek olive oil world, it has helped companies reach consumers in more than 220 countries around the globe.